‘Nothing to see here’: How organisations position ageism as an individual issue

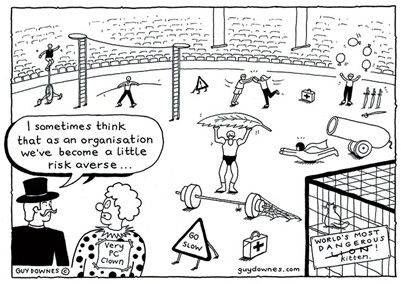

Risk averse recruitment decision-making as a case in point.

The Issue

There is much current discussion about skills and labour shortages. Employers believe that the cut-back in Government-sponsored skilled migration programme is the primary cause of our labour crises. Yet, the potential recruiting of younger and older workers as part of the solution remains overlooked. The lack of work experience of young people is often cited as a problem. Perish the thought of investing in training and development to grow a more self-sufficient local labour force. Pension restrictions, on the other hand, are raised as a primary reason preventing older workers wanting to return to paid employment. This rationale, however, does not explain all the older people not on a pension who wish to work but are still overlooked by recruiters.

We’ve Reduced Age-bias to a Personal Issue

Government, the media and industry have become very skilled in ‘personalising’ the issue of age-bias. Responsibility for the lack of progress in tackling ageism has been transferred to individuals. In this way labour shortage issues become positioned as a supply side problem not a demand side issue.

The tendency to personalise age-bias allows ageism to flourish in organisations. For some time organisations have deflected the issue of ageism to the existence of ‘unconscious bias’ amongst business decision-makers. Offering ‘Unconscious Bias’ training to employees represents a symbolic business act demonstrating commitment to workplace inclusiveness, reinforcing ‘bias’ as a personal issue and removing an obligation to address structural work environment barriers which reinforce ageist thinking within employees.

Organisations have embraced ‘Unconscious Bias’ training as it removes accountability to review the habits, routines, processes, precedents and beliefs that regulate the everyday work environment. Ignored is the conditioning influence of entrenched workplace structures on individual choice and decision-making. In the workplace environment, an employee’s choice to behave in a specific way can be understood as a deliberate, conscious and conditioned response rather than a display of ‘unconscious bias’. This employee behaviour was clearly captured in our PhD research which demonstrated the impact of an organisation’s work environment on negative HR perceptions of both younger and older workers through the prism of ‘talent’ meaning.

Recruitment decision-making is an example of ageism built into everyday work habits. A propensity for risk-aversion in hiring decisions is an implicit structural barrier for the employment of the younger and older worker.

Risk aversion in recruitment decision-making

Personal accountability for making decisions is recognised as a major contributor to anxiety which in turn encourages more risk averse decision making. Decision makers feel compelled to be able to justify and legitimate their decisions. Research has established that recruiters rely on past practice in selection decision-making as a way of reducing hiring risk and personal accountability for a poor recruitment outcome. A reliance on past practice acts as a deliberate restriction on the range of people recruiters are prepared to consider. If young inexperienced people or older experienced people have not found themselves on past recruiter short-lists, a very high probability exists they will not then find themselves on contemporary recruitment short lists. Numerous organisation factors have been identified to explain this deliberate recruitment decision-making behaviour:

· ‘Organisation memory’ represents the stored information from an organisations past that can be brought to bear on present decisions. Over time different senior leadership groups embed within the organisation a set of recognised values and principles that pass down to subsequent generations assisting in the future preservation of the organisation. Supporting this behaviour, research notes a rise in the use of past success models and the selection of future leaders who have the same skills as past leaders. If an organisation memory does not value young inexperienced or older experienced job candidates this discourages recruiters from entertaining alternative views of their potential worth.

· Motivational theory highlights our behaviours are shaped by seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. Reliance on past practice in selection-decision-making is an example of recruiters exhibiting an avoidance outlook in their hiring decisions. Recruiters see little personal reward in challenging prevailing recruitment practices.

· Research reveals that manager recruitment decisions are conditioned by earlier negative experiences in managing diversity in their organisation. A possible negative interaction with an individual or small group of individuals sometime in the past becomes extrapolated to represent a negative stereotype for a complete diversity cohort and reason not to hire. This is an example of a very ‘conscious’ bias at play in the workplace.

· PhD research has highlighted how risk averse hiring is reinforced through a strong preference for group-based hiring decision-making. Organisations have been found to deliberately use the social control force of group pressure to influence individual views thereby minimising challenges to existing recruitment thinking and practices.

How This Organisation Practice Maybe Harming Your Business

Every day more evidence becomes available demonstrating the tangible returns of age-inclusive workforces to business. Examples include:

· In 2020 the OECD determined that a company with a 10% higher share of workers aged 50 and over than the average is 1.1% more productive and has 4% lower labour turnover.

· The Boston Consulting Group in 2018 concluded that companies with above average diversity on their management teams report innovation revenue that is 19% higher and profit margins that are 9% higher than companies with below-average diversity.

· A major study over a decade and involving 18,000 German companies concluded that increasing age diversity has a positive effect on company productivity for professional, managerial and services work.

· Research has established that creating a positive work environment for multiple generations improves knowledge sharing and transfer.

Do you know how much your existing recruitment practices may be penalising your business?

If the above research outcomes have made you reflect on your recruitment practices, please contact us and let us help you take practical steps to transform your workplace into an inclusive age-neutral one that develops your competitive and performance capability.

Selected References

Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P., & Mundell, B. (1995). Strategic and tactical logics of decision justification: power and decision criteria in organisations. Human Relations, 48(5), 467-488.

Backes-Gellner, U., & Veen, S. (2013). Positive effects of ageing and age diversity in innovative companies - large scale empirical evidence on company productivity. Human Resources Management Journal, 23(3), 279 - 295.

Bolander, P., & Sandberg, J. (2013). How employee decisions are made in practice. Organization Studies, 34(3), 285-311.

Gochman, I., & Storfer, P. (2014). Talent for tomorrow: Four secrets for HR agility in an uncertain world. People & Strategy, 37(2), 25-28.

Hessell, T. (2021). ‘Talent and age: How do Human Resource Manager meanings of talent influence their perceptions of older workers?’ PhD Thesis. University of Newcastle, Australia

Kuhn, K. (2015). Selecting the good vs rejecting the bad: Regulatory focus effects on staffing decision making. Human Resource Management, 54(1), 131-150.

Maclean, M., Harvey, C., Sillince, J. A. A., & Golant, B. D. (2014). Living up to the past? Ideological sensemaking in organizational transition. Organization, 21(4), 543-567.

Noon, M., Healy, G., Forson, C., & Oikelome, F. (2013). The equality effects of the 'hyper-formalization' of selection. British Journal of Management, 24, 333-346.

OECD (2020). Promoting an Age‑Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer Report

Walsh, J. P., & Ungson, G. R. (1991). Organizational Memory. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 57-91.

Zheltoukhova, K., & Baczor, L. (2016). Attitudes to employability and talent. Retrieved from https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/attitudes-to-employability-and-talent_2016_tcm18-14261.pdf